Looking for the myths of today, a space mission

Hunting for myths is like looking for the Yeti on Everest, if you're lucky, at the top you'll find your neighbor who annoys you every day with his lawnmower. The unattainable is not on the brochures of travel agents, everything else is on the shelf. They advise, the well-informed, to chase the 'trends' and pay submariner's attention to the sonar for 'what's new.' Sooner or later something will appear, they say. All right, in the meantime, I jump back, turn on the time machine. May happen to discover a black hole to make one in the future, after all, it's a matter of navigating the event horizon without getting shrunk like a noodle. Looking for the myths of today, a space mission. Forward, backward all the way.

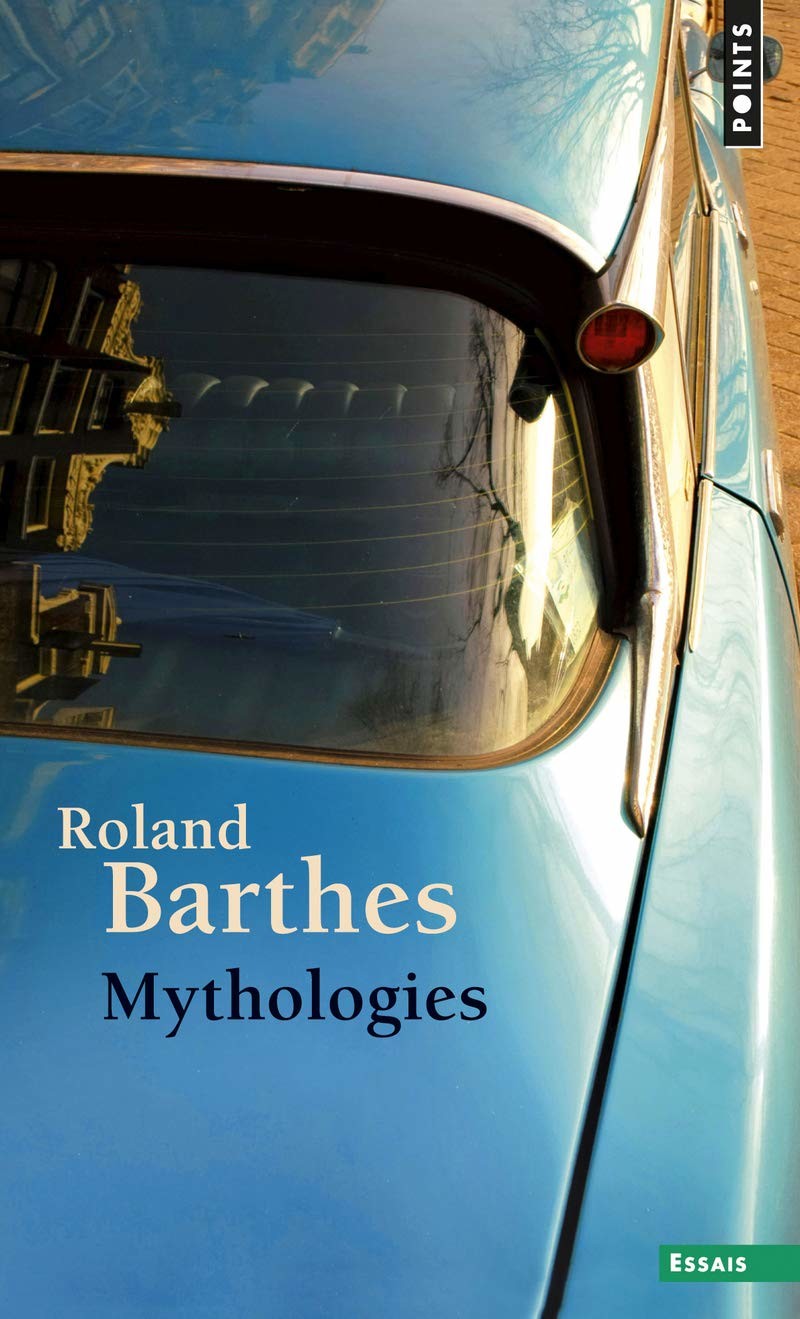

In 1957, Roland Barthes published a book that became the subject of many (vain) imitations: Mythologies. Text and context, object and subject of Western society, were broken down and recomposed by Barthes with the laser beam of language. Barthes, like Paganini, never gave an encore, only once offering insight into his Myth Today; he never updated his work, didn't add any other chapters, characters, words and things. He considered that game on the field of meaning unrepeatable. He exhibited the full repertoire: the baseline shot, the powerful forehand, the sliced backhand, the volley at the net; back and forth, it was a literary and pre-television Wimbledon tournament on the (in)consciousness of bourgeois life, affluence unpacked: voilà! Then it ended, because, in the meantime, semiology changed its intended use; it became an instrument of political battle, an a-critical critique of society, capitalism, everything that, sure, had (and has) too many problems but continues to be the formula of cohabitation of the (all too human) human closest to that thing that needs to be taken care every day: freedom. Beyond it, there were (and there are, we can see), dictatorship and war. Empires and conquest. In Italy, Umberto Eco enjoyed putting into the Bustina di Minerva of the Espresso weekly magazine that is no longer (and much more has also been lost) some amused Barthesian incursions, broken and glued pieces of mass culture, sharp shards of the bottle of everyday life (sure, Eugenio Montale: Meriggiare pallido e assorto / presso un rovente muro d'orto, / ascoltare tra i pruni e gli sterpi / schiocchi di merli, frusci di serpi; To pass noon, pale and thoughtful / near a hot orchard wall / to listen among thorns and twigs / snaps of blackbirds, hisses of snakes).

Like Barthes, Eco still without the name of the rose did not pretend to change the world; he tried to interpret it, to (in)form it, to temper it like the point of a pencil. And wham! He revealed what goes on above and below our talking, aspiring, consuming, buying, the shop of life, the coming and going of the useful and the superfluous. The moving (and not always noble) boundary between need and desire.

On the cover of Mythologies there was (and still is) a Citroen DS, the car with bodywork as never before, with suspension, sexy and a little haughty, supple as in the poem by Pablo Neruda (Brown and agile child, the sun which forms the fruit / And ripens the grain and twists the seaweed / Has made your happy body), a triumph of curves that I would later discover to be fatal in life and Promethean in Ernest Hemingway's writing in Fiesta, with the slightly drunken cat eyes laid on Lady Brett Ashley: “Brett was damned good-looking. She wore a slip-over jersey sweater and a tweed skirt, and her hair was brushed back like a boy's. She started all that. She was built with curves like the hull of a racing yacht, and you missed none of it with that wool jersey.” We'll get back to the boats; on this lonely cruise, it’s now the Citroen DS on the track. Fantomas used to drive one (good heavens, he flew!) and, on the other hand, with that suspension, gently up and down, without the uncomfortable vibrations of cobblestones and Roman tar, the flight was just a matter of checking in the imagination.

Ignition, bend, take off! The mimeograph journalism today would have already used the term “icon”, but the copy and paste of presentism without memory has decided that everything is “iconic”, therefore everything is nothing by usury, lost in the etymological desert; lost is the meaning (that Barthes sought) of a word that derives from the Russian ikona (will it be interpreted as a signal of intelligence with the enemy?) which in turn comes from the history of the Greek-Byzantine εἰκόνα, in the classical Greek εἰκών -όνος, image. Not just any image; not an iPhone pic in Capalbio (beautiful and soulless, like so many others that hook you and reel you in, then abandon you after destroying your illusions), because ikona is a portrait of the sacred, religious subject, object of Byzantine, Russian and Balkan art. What did Donnie Brasco say? “Forget about it!” Film.

The mimeograph journalism today would have already used the term “icon”, but the copy and paste of presentism without memory has decided that everything is “iconic”, therefore everything is nothing by usury.

And today? What are the myths today? Are there any? There sure are! They are everywhere: you can find them among the smartphone, Instagram, pixelated, digitally mastered images. Watching. Until a few years ago, it was always elsewhere: there was a horizon, an external projection, a long beyond something. Between one iPhone model and the next, the gaze has switched to self-tipping mode; the transition from the epistolary novel to the confession on Facebook, from the self-portrait to the selfie-therefore-am philosophy, from the hendecasyllable of the cursed poet to the Checco Zalone comic rapper (Checco Zalone just gets it so well—close your eyes, listen to La barca dell'Oligarca (The Oligarch's Boat), reopen them and look around—surprise!), from the Decadent movement to the decline of language. We could do with a writer of the caliber of Alberto Arbasino, here, now, to shoot the arrow of the post-literary mockery, while alongside the Faraglioni, Checco notes in his logbook that “lo yotto si arresta” (the yacht stops).

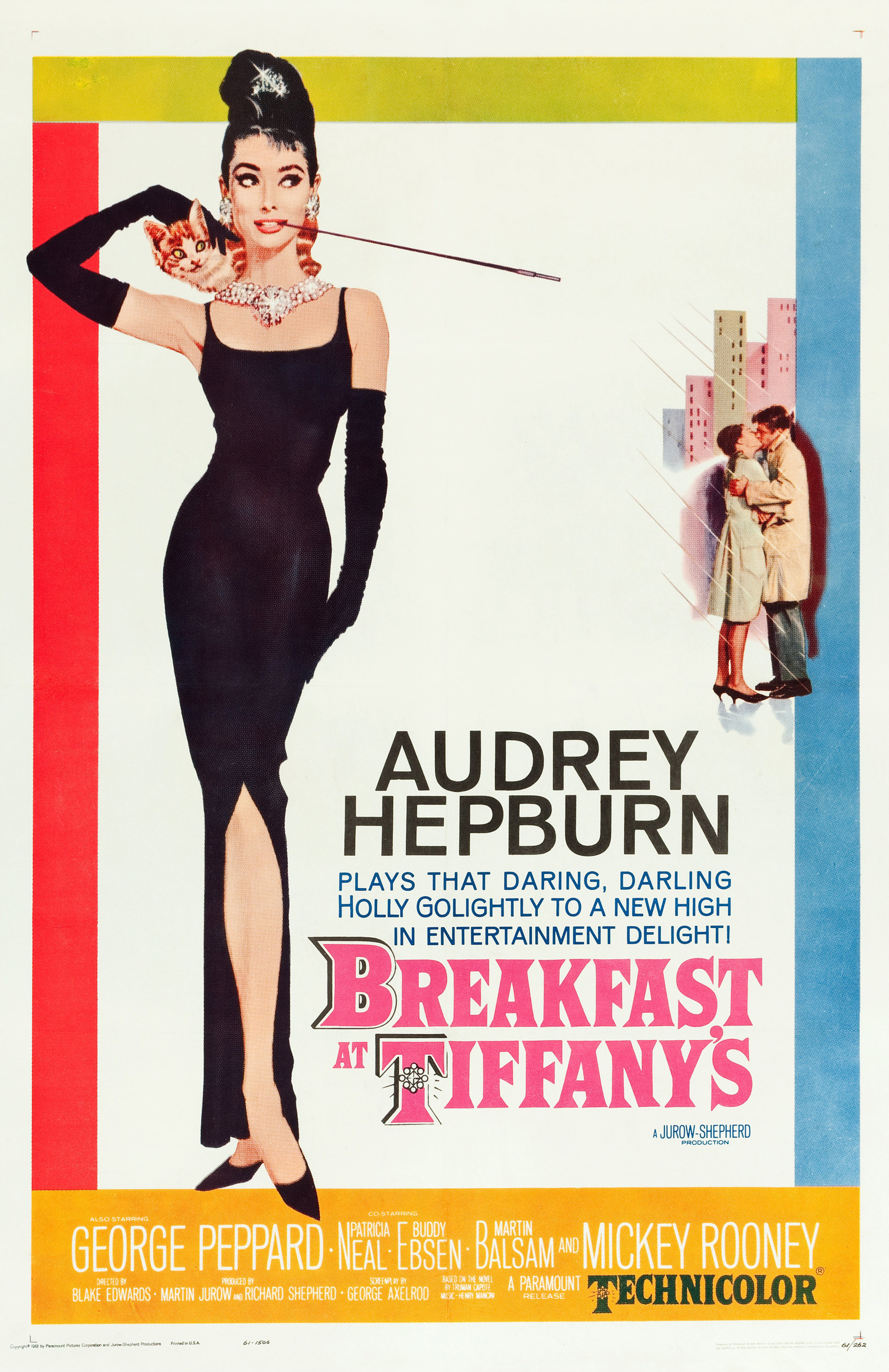

When I was at Panorama weekly magazine, knowing that I wrote about politics (and therefore, “pardefaut”, it was supposed that, coming from 24/7 coverage of the political scene, I would never be able to grasp the refined nuances of those who know all about costume and appearance), I was instructed on the power of 'glam' in magazines that wanted to be 'trendy', on the 'seasonality' of the covers, an editorial mix-and-match breviary with a dollop of “think of Breakfast at Tiffany's.” Jeez! I replied that I had read more or less all of Truman Capote and the 'glam' seemed to me a matter of a column layout in typography; something that had to do with the elusive subject of the story, the writing, the tone, the rhythm, the plot. Then there was image and Breakfast at Tiffany's, it's true, had Blake Edwards behind the camera and George Axelrod's hand on the script sheet; but my modest, disastrous, antiquated idea was that it would never have been made without that novel that gushed rivers of alcohol, solitude, flirting with the chèque, chic obsessions, shocking love. What shone about the jewels was the impossibility of buying them without committing a robbery. Except love, found at the last minute, with a cat tight in her arms, in the rain. The myths of today; the factory of imagery. Where am I? You have to run back to find someone to imitate, the reference points; you know, that thing that we used to describe as “maestro” or “master”.

An example? Take Ian Fleming—to stay on the safe side—a life shaken and not stirred: spy, commander, journalist, sports car (Aston Martin DB5 vs Ferrari F355 GTS in Die Another Day), perfect tuxedo, heavily armed against love (he crashed just once, suffered irreparable damage—after all, she was Vesper and his weakness was understandable)—, villa in Jamaica, too many cigarettes and stories of whiskey gone bad (long playing by the singer Sergio Caputo, 1988), sea, ink and Goldeneye. The 007 cocktail, once again, is the writing. And the film. And the music. And Matera, Italy, which is the set of the action in No Time to Die. Take one! Shooting begins. Those who have already found all of today’s myths, cataloged them, lined them up, arranged them in a periodic table of elements of which only they understand the alchemy, will say that it is useless to dwell on the word, because in the end, in our accelerated time, it is the image that matters. True, but even the 'figure' obeys a certain grammar: the image is the first sign, that of our very distant ancestors left on the stones, on the walls of caves that were once 'home'.

The stones speak. Just browse through Figure, the book by Riccardo Falcinelli, and you enter a maze that leads us from the Renaissance to Instagram. Do not underestimate 'metaphysics of bowls' (Metafisica delle ciotole) and do not be surprised if 'emptiness befits fawns’ (Il vuoto si addice ai cerbiatti), calibrate the weight of your gaze on the 'Hitchcock scale’ (La bilancia di Hitchcock). Precision and imagination. Also 'bread, love and...', for those who have not forgotten Luigi Comencini, Gina Lollobrigida and Vittorio De Sica, the 'pink neorealism' of Italian film. A myth without seriality. The woodpecker pecks the trunk—one and two, three and four—the question settles on the branch in front of the window: but where are the myths of today? They are the ones that last. Considering the mortality rate of the so-called “cool” ideas that find space in the post-cathodic hospice of the pre-deceased, those who remain outside the tele-moratorium are all fine and are for the majority myths in the shade. You often discover them in unexpected pages, set in the landscape of eccentric authors.

In 2012, Camille Paglia wrote a book called Glittering Images: A Journey Through Art from Egypt to Star Wars, another brightly-lit piece in an ideal library of imagery, a dance of fireflies. It takes off in the land of the pharaohs, explores the tomb of Nefertiti, jousts with the centuries, flies away from the solar system and lands on George Lucas' red river in Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith. The triumph of digital art, the educated will say, always ahead of the game, in search of 'novelty'. Not really; the medium isn't always the message, even if McLuhan’s premonition was all right.

Where are the myths of today? They are the ones that last. Remain outside the tele-moratorium are all fine and are for the majority myths in the shade. You often discover them in unexpected pages, set in the landscape of eccentric authors.

Paglia, multifaceted explorer of contemporary culture (the jury’s open on Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson) finds 29 subjects who have the gift of the eternal flame and among these, 5 are linked to Italy: Donatello and his Mary Magdalene (Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence); Titian and Venus in the Mirror (National Gallery of Art, Washington DC); Gian Lorenzo Bernini and the Chair of St. Peter (St. Peter's Basilica, Rome); Agnolo Bronzino and the Portrait of Andrea Doria as Neptune (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan); the Laocoön for centuries in search of an creator (Vatican Museums, Rome). Who has seen them? Don't cheat: we are pros at poker.

The obsession with the new, which must be the ‘very latest, of course’, ends up distracting us from seeing what matters, listening to who is singing, reading the bits left over. “One sees clearly only with the heart. Anything essential is invisible to the eyes,” wrote Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in The Little Prince. We are all blind. And free from palpitations. Following the 'trends', sure, but what will these decisive 'trends' be without the long wave of the past that never dies? Nothing: matches that go out quickly in the dark. We like flames that last. Il viaggio in Italia, the discovery. At the cinema: 1953, directed by Roberto Rossellini, with Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders; an English couple in crisis, wounded, lost, wandering between Naples and Capri, reunited in a final scene of unexpected love. In literature: 1957, Guido Piovene, a three-year report on the miracle of reconstruction, the boom, the fall and rising again after the war. Italy in black and white that was shooting in color.

The journey round Italy can only (re)start with Dante Alighieri. Dante's country is not a literary sidereal elsewhere; the places of the Divine Comedy are our map inside and out, a very present yesterday that is made and unmade every day: a living map. Giulio Ferroni drew this map in L’Italia di Dante (Dante's Italy), a geo-literary sculpture that (re)discovers Italy among the chained rhyming triplets into which Ferroni dives, later to return to the surface with a ligature of the poetic remote past with the present in prose. Diary, notebook, correspondence, confession. Each stop has a before, a during and after Dante; it can be reached without satellites and voice commands, following plots, flashes and open spaces, memory and nowadays. A journey, sure, because poetry is always a tangible journey into the void that it opens up with its greatness. Here, you stroll through the place that Dante first measured in the infinite formula of the belpaese; the centuries have not worn it out: the country is beautiful. 'Dante's Italy' starts from Naples, where there is (and there isn't) the tomb of Virgil and the tomb of Giacomo Leopardi, an array of apparitions, disappearances, silent presences and noisy absences in the city that “perhaps more than others, arouses desires, nostalgia, hopes, return of something lost.” We are here, between Hell, Purgatory and Paradise. Myths of today? What a question! The Bel Paese!

Read

13 giugno 2024

13 giugno 2024